Burgers Are Forever

From Ancient Rome to TikTok: Australia's Burger Obsession

Words by Sofia Levin

Images by Hayden Dib, Sofia Levin & supplied

Last updated 18.09.2025

Burgers aren’t “trending” in Australia – we’ve been obsessed with them for nearly a century. Today, they rack up views on TikTok and reside on fine dining menus, but how did burgers get here? And where are they going?

The hamburger has a blurry history. One could be a real stickler and trace its origins back to the 1st century AD, when Romans made isicia omentata – meatballs flavoured with spices, wine and garum. In 1747, a recipe for “Hamburg sausage” appeared in Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cookery, describing a smoked sausage made with minced beef and served on toast. Fast forward to the turn of the 19th century, when German immigrants brought “Hamburg steak” to the USA. The term entered the Oxford English Dictionary in 1802, defined as: "a hard slab of salted, minced beef, often slightly smoked, mixed with onions and breadcrumbs." If isicia omentata was the hamburger’s “Roman Empire”, then G. A. Coffman’s 1845 invention of the meat grinder was its Industrial Revolution.

There are two competing burger invention claims from 1885: the Menches Brothers reportedly created the burger at a New York state fair after running out of sausages, while Charlie Nagreen – later known as “Hamburger Charlie” – is said to have squashed a meatball between bread so customers could eat while walking around the Seymour Fair in Wisconsin. In 1891, Oscar Weber Wilby cooked flame-grilled beef patties in a bun to celebrate the Fourth of July. Then in 1904, Fletcher Davis claimed he'd been serving ground beef sandwiches since the 1880s at the St. Louis World's Fair in Missouri.

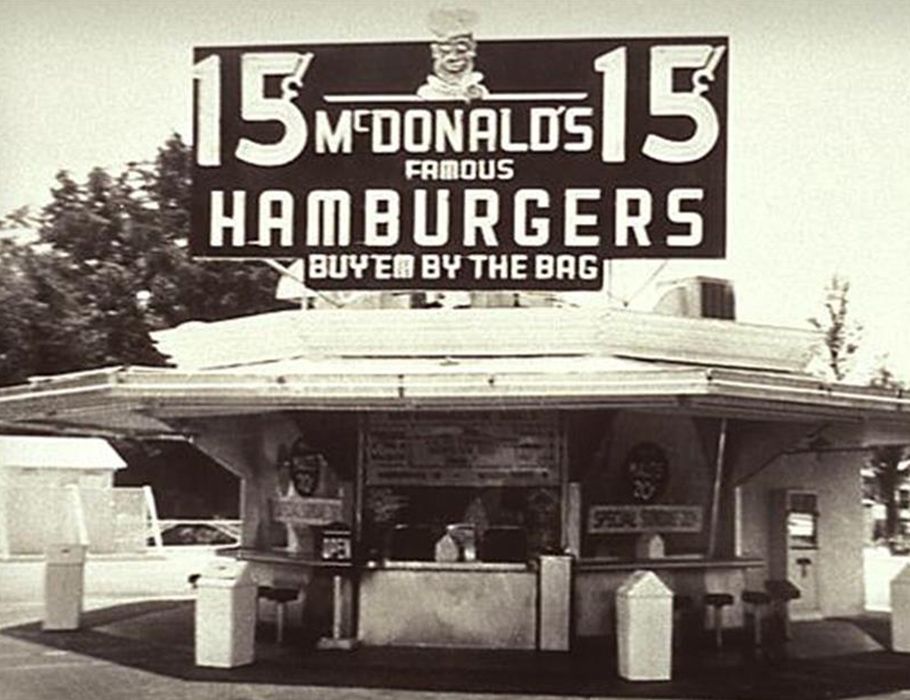

Regardless of who took one small step for burgers, White Castle took the giant leap in 1921 when it opened the earliest example of a dedicated hamburger restaurant in Wichita, Kansas. It changed the course of burger history, before McDonald’s took the reins. The global fast-food chain began in 1948 when the McDonald brothers switched from a barbecue shack to selling burgers in San Bernardino, California. In 1955, Ray Kroc joined and took the business global, despite being a bit of a dick (I highly recommend watching The Founder, if you haven’t already).

Burgers Down Under: Would You Like Beetroot With That?

Australia's burger journey began in earnest with the opening of Andrew’s Hamburgers in 1939 in Melbourne. Prior to that, burgers could only be found at fish and chip shops. The shop’s namesake, a Cypriot immigrant, didn’t like the smell of fish, and so opened his souvlaki and burger shop in Albert Park. It’s still there today selling the latter. Burgers continued to gain popularity in post-war Australia due to growing cultural ties with America. The Aussie burger with “the lot” – which many are horrified to hear includes sliced beetroot and pineapple – became iconic. These inclusions were likely due to surplus tinned goods from Edgell and Golden Circle, which opened canneries in the 1920s and 1940s. Others claim it was a prank on American troops that stuck around – a stunning example of Australians’ commitment to a gag.

In 1971, Sydney became home to Australia’s first McDonald’s, and Hungry Jacks (which would have been Burger King if the trademark wasn’t already taken locally) opened in Perth. As fast food infiltrated the landscape, burgers began to seep into pubs, cafes and restaurants, while Aussie burgers with the lot became the domain of neighbourhood burger shops, fish and chippers, and milk bars.

The Health Kick & Gourmet Boom

In 2004, amidst growing health concerns around fast food, Morgan Spurlock released his documentary, Super Size Me. In it, he eats only McDonald's for a month to horrifying effect. It was perfect timing for Grill’d, which opened in Australia that same year promoting “healthy burgers”. This coincided with growing consumer interest in ingredient quality, fuelled by health concerns and the rise of food-centric entertainment (like MasterChef Australia, launched in 2009) and the sexification of the hospitality industry.

The American Revival

Around this time, Aussie chefs and operators were returning from trips to the U.S. with newfound love for simple, American-style burgers. They opened new shops – more of a revival than a so-called trend. Smash burgers, invented in Kentucky in the 1960s, began to flourish. Made by flattening a minced beef ball to fast-track the Maillard reaction, these days they’re synonymous with American chains like In-N-Out, Shake Shack, and White Castle. One of the pivotal players in this evolution from fast food to gourmet was Melbourne’s Huxtaburger, opened in 2012 by the team behind the now-closed hatted restaurant, Huxtable.

“They were the first to really push an American-style with a different type of bun… a softer brioche-style that allowed it to be less intrusive,” says burger expert Jimmy Hurlston, co-owner of Easey’s in Collingwood. “It didn’t make you feel sluggish afterwards. And it was more like the burgers we saw in movies.”

In 2013, Jimmy quite literally wrote the book on burgers – The Burger Book. He samples at least a burger a day, and estimates he’s eaten more than 25,000 burgers over the last decade.

“In Australia specifically, I think the burger thing has never really gone away, however it made a switch in style and appearance,” he adds.

Dani Zeini played a major part in popularising American-style burgers Down Under. He opened the first Royal Stacks in Melbourne in 2016 after a revelatory burger experience in the U.S. By the end of 2025, there will be 20 stores in Victoria, with plans to reach 50 within five years in the state.

“My experience with burgers in Australia was either a Macca’s or ‘Alexi’ at the fish and chip shop. Then when I went to the States for the first time and had a proper American burger, it was un-friggin-believable,” he says.

The same way people insist that you need to try an In-N-Out Burger when you go to America, Dani hopes one day they’ll say that about Royal Stacks in Australia.

The Burger Shake-Out

Following the burger boom, Jimmy noticed specialised burger shops drying up from around 2017 to the start of Covid. It was partly due to UberEats launching in Australia in 2016, which, as Jimmy puts it, “ripped the soul out” of local burger haunts. Delivery also saw the rise of dark kitchens. The burger places that survived had two things: consistency and a point of difference.

“There were too many places that were the same. We had a train carriage on the roof, which certainly helps, because I would never say that Easey’s is the best burger in Melbourne. It's just a consistent burger,” says Jimmy.

Even being a fine dining chef doesn’t guarantee success: Australian chefs Neil Perry and Shannon Bennett both opened chains when burgers were peaking (Burger Project in 2014 and Benny Burger in 2017 respectively), but all stores have since closed.

The Fine Dining Burger

Melbourne’s Cutler head chef, Shun Young, explains: “You'd be really surprised; a lot of chefs don't know how to do medium rare on a burger patty. It has to be consistent. From the first burger to the hundredth burger, to always be the same, that's the hardest part.”

Over the last decade, white-tablecloth restaurants have embraced the burger. Cutler made its $35 burger available in the dining room when it switched from a set menu to a la carte in 2024 (the burger was previously only available at the bar since it was introduced in 2016). The restaurant is part of restaurateur Andrew McConnell’s Trader House group, along with Gimlet, which serves one of the city’s most famous burgers, available for $28 exclusively during its late-night supper service on Friday and Saturday.

High-end chefs may have embraced the burger as a vehicle for showcasing premium ingredients, but it’s also a response to changing diner habits. When money is tight, we yearn for simpler times; anything nostalgic – such as burgers – is flung into the zeitgeist. As the line between casual and upscale dining blurs, fine dining venues are recognising the cultural cachet and commercial power of a perfectly executed burger.

“We are refining what fine dining means in 2025,” says Shun. “If we can cook a burger well, the rest of the meal will be excellent. We have guests who have the burger as the entrees; the burger as their side together with the mains; they cut it up and the whole table shares it. It’s about flexibility.”

These days, menus proudly list if beef is wagyu or angus, and whether a bun is brioche or potato. The burger has become a measure of a restaurant’s ethos, but perhaps the factor that’s had the greatest impact on burger culture is social media.

The Social Era

“All of a sudden, we've been able to scale word-of-mouth,” says Beatbox Kitchen founder, Raph Rashid. But that virality is a double-edged sword. As Jimmy puts it: “It doesn't have longevity necessarily, but if you need a spike in business, then it's definitely something you need to be looking at. Then it's on the operator: are you going to create a product that people are going to continue talking about and come back for?”

At the end of July 2025, that’s exactly what Oğulcan (OJ) Atay and chef Çağri Ergin did when they opened Charrd in Melbourne’s Brunswick East. Little more than a burger window, it shares a kitchen with Yakamoz, the Turkish restaurant OJ owns with his father. Within a couple of weeks, they were selling nearly 1000 burgers a day. Within two months, they were ranked the 14th best burger in the world by London’s World’s Best Steaks.

The signature burger was introduced to the Yakamoz menu, but quickly became popular enough to inspire OJ to open a separate service window under a new business name.

“A lot of Charrd’s customers don’t even know that there was a burger (at Yakamoz), they’re all just new customers who are seeing these videos that people are posting,” says OJ. “With Yakamoz, it was a lot harder (when we opened) because we were convincing people to eat a new cuisine… with Charrd though, it was a lot easier.”

The best time to start lining up, according to OJ, is at least 30 minutes before Charrd opens.

“Would people be queuing out the front that long for anything else? No,” he admits.

The Future of Burgers

Dining has become a favourite outing, while social media has simultaneously made discovering new places to eat more accessible than ever. When Raph opened his Beatbox Kitchen food truck in 2009, customers would stalk him on Twitter to find out where he was pulling up; now the shareability of social media means they don’t have to search for their next meal – it’s delivered straight to our feeds and direct messages.

“Now food is an activity that we do. It’s $20 or $30 bucks, and you have an experience: your food comes on a plate. You get to chill. You get to take some photos. That's fun, you know?” he says.

The last 15 years have seen burgers pioneer two paths: shops fuelled by social media, and produce-focused burgers worthy of top restaurants. But regardless of how many burgers come and go, they will remain a staple of Australian dining – the same way they have for nearly one hundred years.

“The burger scene’s here to stay, it's not going anywhere,” says Dani. “I still haven’t seen somebody eat a burger and have a bad time – it's a ‘happy meal’.”

Want to know the latest burger trend in Australia? You'll find it at the most unexpected location. Get the scoop here.

Join the Eat Curiously Movement

Subscribe to the food newsletter that goes deeper.