To Black Market

Communism & The Black Market: Why Cuban Food Gets A Bad Rap

Words by Sofia Levin

Images by Sofia Levin & Greg Levin

Tourists might have access to lobster and beer in Cuba's state-run restaurants and hotels, but you won't find them in smaller paladares, where locals are sometimes forced to turn to the black market for basic supplies.

“Let me explain to you the situation with the milk and the eggs,” says our Airbnb host in Cienfuegos.

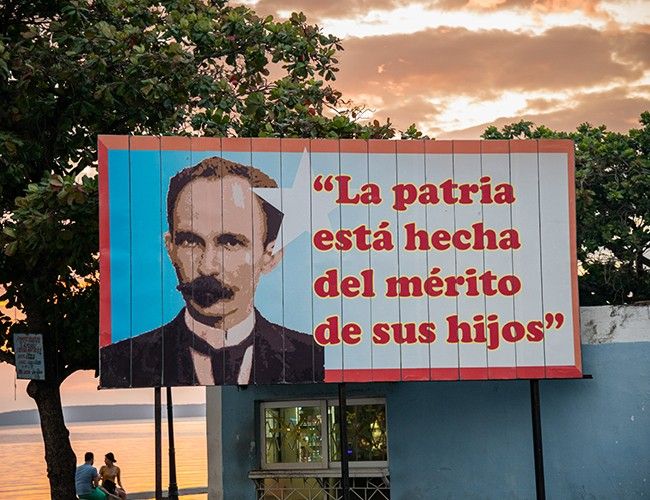

That’s as much information as I plan to share about him, because in Cuba it’s unwise to criticise the government. The people are fiercely nationalist and support their socialist government, but not all think the ideology is being effectively implemented. When locals want to complain the keep it general, lamenting, “Qué están haciendo?” which means, “What are they doing?”

We’re sitting in a small patio behind a spacious, four-bedroom house. The heat of the day hasn’t hit yet, but the sun-faded peach walls are a reminder that we’re in the tropics. As we sip fresh pineapple juice, our host asks us how we would like our eggs. Poached is not an option.

“The eggs we make with powdered egg. So you can only have omelette or scrambled. We are rationed five eggs per person every month, and you’re allowed to buy more, but I haven’t seen any for days.”

There’s no fresh bread, either. Stale slices and inedible rolls are common over the next 24 hours. We’re told that the bread mill needs new parts, but the government hasn’t paid for them, so they’re not operating. He’s unsure why there’s an egg shortage.

“Can you buy chickens?” I ask.

“It’s not so easy. You need to meet regulations and they come and check. We live in this house but most people live with lots of family in apartments.”

You also need permission to fish. Most of the seafood is exported, and what’s left goes to state-run restaurants and hotels. Crustaceans are a US$80 billion export industry. There’s plenty of lobster on the menu in Cuba for tourists, but locals stick to eating pork and chicken, when available. Locals also can’t buy lobster, but as a tourist you’ll see it everywhere priced from $10 to $25 CUC.

Cubans refer to la lucha, the daily struggle for food. They line up for rations like beans, rice and milk, but many paladares – private restaurants run from people’s homes – get around it by buying food a la izquierda, or “on the left”. There’s a thriving black market throughout Cuba, a necessary means if one wishes to access products controlled by the government.

“You’ll go into a supermarket owned by a member of the communist party to buy cheese and there isn’t any. But then when you go out the front, all of a sudden there will be black guys – they are usually black – saying, ‘cheese, cheese, cheese,’ but it’s very expensive,” says our host.

According to him, it’s common for state-owned stores to hold back certain products to sell on the black market, and ingredients like cheese and seafood, which would ideally be on a paladar’s menu, are either difficult to source or unaffordable. If you walk into a supermarket in Havana, chances are the shelves will be more than half empty. Those that are stocked are stacked with tinned goods, cans of soft drink and long-life goods.

“We used to serve dinner here, too, but it got too hard. Beef is CUC 9 per pound. Pork is 3 CUC per pound. And shrimp? There used to be a song about how good the shrimp was in Cienfuegos in the 1930s. But not anymore.”

“What about lamb?” I ask.

He shakes his head. “I haven’t seen lamb in a long time.”

I tell him we’ve been trying to find the national beer, but that no one seems to have it.

“You need to have a contact,” he explains. “There is not enough beer for everyone, so you need to have a contact, and you need to buy a lot. You could have 1 million pesos, but it won’t buy you beer unless you have a contact.”

In April 2018, Cuba’s First Vice President Miguel Díaz-Canel replaced 87 year old Raúl Castro, who took over from his brother, Fidel, in 2006.

Our host says that 1980 to 1989 was the best decade for food in Cuba thanks to Russians, who underpinned the economy with oil. “Cuban was a thorn in America’s side,” he tells us. The Russians left after the fall of the Berlin Wall and collapse of the Soviet Union. “The Special Period” followed.

“That was a bad time,” our host says. “We had blackouts for 20 hours a day. We couldn’t find food, we couldn’t find anything.”

I add sugar to my coffee as I listen. I’m usually a “black, no sugar” kind of girl, but it’s needed. Cuba used to be one of the largest producers and exporters of sugar in the world. Now it imports sugar from France. Imported food makes up between 70 to 80 percent of what’s consumed in the country. Perhaps eggs will be next.

Around the World in 80 Lesser-Known Melbourne Restaurants

FREE food guide when you subscribe.